Striking a Balance: The Art of Effective Decision Making

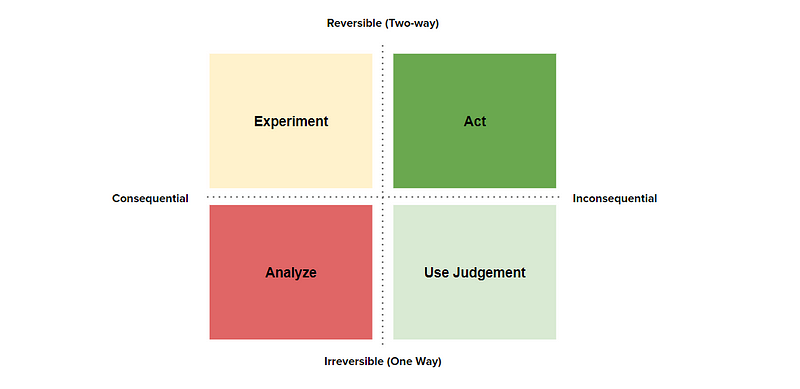

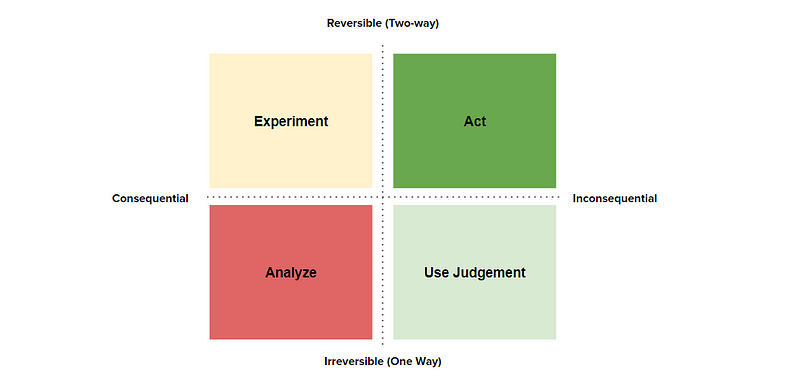

Integrating the dimensions of consequentiality and reversibility in decision-making can help provide clarity and simplify your approach.

I offer consulting services on growth strategy, pricing strategy, unit economics, and more. Visit my website for more information.

We’ve all experienced situations where we have hastily jumped into making a decision without fully comprehending the scope or characteristics of the decision first. The consequences of this can be quite significant, depending on the decision being made. In this blog post, I share a simple framework that integrates the dimensions of reversibility and consequentiality. Evaluating your decision along these lines is a great first step to understand how best to approach the decision.

Type 1 (One Way) vs Type 2 (Two Way) Decisions

Understand that some decisions can be reversed. “Type 2 decisions” are two-way decisions that can be reversed. If you have a suboptimal Type 2 decision, you can reopen the door, and unwind the consequences. Because of this, these decisions should often be made fairly quickly. Conversely, “Type 1 decisions” are one-way decisions that cannot be reversed. These decisions must be made with careful deliberation. Understanding the difference between these types of decisions is important because it helps you decide how much time to spend on a decision.

Applying the wrong decision-making framework can come with huge costs. If we mistakenly apply a one-way decision framework to a two-way decision, we may become slow and overly cautious. On the other hand, if we mistakenly apply a two-way decision framework to a one-way decision, we may take on excessive organizational risks. As organizations grow, there is a tendency to turn all decisions into “Type 1 decisions” that are made methodically and with great deliberation. The end result, however, is slowness and diminished innovation.

Correctly identifying the appropriate framework is essential to strike the right balance between agility and risk management.

Consequential vs Inconsequential Decisions

Consequential decisions are those that carry substantial weight. These choices often involve critical matters that impact the company’s future. Examples include determining the launch of a new product, selecting an investor, or assigning a company’s marketing budget. These decisions demand careful analysis, extensive research, and an evaluation of risks and rewards.

On the other hand, inconsequential decisions are less significant. These decisions encompass smaller-scale matters that contribute to the overall functioning and efficiency of the organization. Examples might include selecting seating arrangements for a meeting or choosing snacks for the office.

Putting It Together: Consequentiality vs Reversibility

Integrating the dimensions of consequentiality and reversibility in decision-making can help provide clarity and simplify your approach.

Consequential and Reversible Decisions (Experiment)

In situations where the decision carries significant consequences but is reversible, adopting an experimental approach is prudent. This involves making a prompt decision but setting clear milestones or checkpoints to review and adjust as needed. By embracing experimentation, businesses can learn from real-world outcomes, adapt their strategies, and iterate towards optimal solutions. This approach balances the need for agility with the ability to course-correct based on tangible results.

Imagine a marketing campaign for a new product. The decision to allocate a significant budget carries significant consequences. Adopting an experimental approach can enable learning, adaptation, and optimization throughout the campaign.

Consequential and Irreversible Decisions (Analyze)

When faced with consequential decisions that have long-lasting or irreversible impacts, a thorough analysis is crucial. These decisions often involve substantial resources and long-term commitments, making it important to conduct extensive research, gather relevant data, and seek expert opinions. Taking the time to carefully evaluate the options and their potential outcomes allows for informed decision-making and mitigates the risks associated with irreversible choices.

The decision to acquire another company has a major impact on finances, resources, and company structure. Careful due diligence, consideration on market trends, and expert opinions is needed to ensure that the decision maximizes ROI for the organization.

Inconsequential and Reversible Decisions (Act)

In situations where decisions are inconsequential and can be reversed, a more spontaneous approach is appropriate. These decisions often involve minor operational matters or routine tasks. Since the impact is minimal, relying on quick judgment and acting promptly, with an emphasis on speed of learning and iterating, allows for efficiency and keeps operations running smoothly. By promptly addressing inconsequential and reversible decisions, organizations can maintain agility and focus on more critical matters.

Choosing the seating arrangement for a team meeting may contribute to team efficiency but has minimal impact. Acting promptly and using quick judgment is appropriate.

Inconsequential and Irreversible Decisions (Use Judgment)

Although inconsequential, some decisions may be irreversible, requiring a balanced approach. In such cases, utilizing available data and exercising judgment is crucial. While the consequences may be minor, making hasty or careless decisions can still lead to unintended complications. Employing sound judgment, based on the information at hand, enables efficient decision-making while minimizing the potential for unnecessary disruptions.

The specific date of the launch falling on a Tuesday vs Wednesday is irreversible once communicated to stakeholders, but also fairly inconsequential. Using judgment on readiness is critical, but overanalyzing the decision would be a poor use of resources.

Common Pitfalls

The three most common pitfalls are when companies prioritize thoroughness over speed due to an over-indexing on one of the two dimensions and when stakeholders are misaligned on the framework that should be used.

Consequential, yet reversible: Seeking certainty and fearing the negative outcome because the decision is consequential can be problematic if the decision is also reversible. You can miss out on valuable opportunities. Fast is not always reckless. In these situations, being lean, fast, and then iterating, pivoting, or expanding is most valuable.

“If you’re good at course correcting, being wrong is less costly than you think, whereas being slow is going to be expensive for sure” — Jeff Bezos

“A good plan, violently delivered now is better than a perfect plan next week” — General George Patton

Irreversible, yet inconsequential: Over-indexing on a decision being irreversible when it is inconsequential can also be problematic. If the decision is inconsequential, use your best judgment and move forward, prioritizing efficient progress.

“Sometimes the best decision is to make a decision and move on.” — My therapist

Misalignment on the decision framework: It is easy to know when a decision is consequential to you but it is less obvious to recognize when a decision is reversible, especially if you are generally risk-averse. Making sure that you are on the same page as others on the decision framework being used is critical to avoid conflict. Going slow when others want to go fast can lead to frustration.

Frequently, these traps arise due to the incentives and risk tolerance within a company. Successful organizations, such as Amazon, emphasize the importance of taking decisive action while also fostering a patient and nurturing environment. I have written about Amazon’s decision-making culture extensively in this blog post. This post is my most viewed article of all time and is worth the read!

When to Decide?

If you want some quick mental models on when to decide, put these in your back pocket:

If the decision is reversible, make it as soon as responsible

If the decision is inconsequential, make it as soon as possible

If you are no longer gathering useful information, make the decision

If you are about to lose an opportunity, make the decision

If you know what to do, make the decision

Conclusion

Mastering the art of effective decision-making is an important skill. Going forward, I encourage you to adopt the 2x2 decision-making framework and use it as a tool to map out your decisions. By documenting your thoughts and considering the various dimensions of each option, you can gain clarity and make more informed choices. I’ve created a simple template that you can download to organize your thinking. Good luck!

Special thanks to Ben Katz for his feedback on this post. He has a great post on decision making himself linked here.