The Importance of CAC Payback in Today’s Market Environment

In today’s environment, CAC payback has huge implications on a company’s ability to scale efficiently. Cash efficiency is king!

Over the last few years, LTV / CAC has become the gold standard metric to determine the growth and profitability potential of a direct-to-consumer business. Somewhere along the way, the concept of CAC payback got lost, but it has huge implications on a company’s ability to scale efficiently. In today’s evolving macro environment, specifically highlighted by the recent emphasis on cash flow and profitability, cash efficiency is becoming much more important. In this post I’ll: 1) share why long CAC payback times can be a silent killer to growth and efficiency, 2) identify the major market forces that can erode unit economics, 3) highlight key benchmarks for a healthy business, and 4) share case studies and examples of companies that fall along the spectrum.

LTV / CAC + CAC Payback

While both of these metrics are important to monitor, they need to be taken together to understand the health of a business. Together they represent the margin efficiency of growth combined with the cash efficiency of that growth.

LTV / CAC: Represents the margin efficiency of an investment to acquire customers (ROI)

CAC Payback: Represents the cash efficiency of spend to acquire these customers

If you want a refresher on core concepts around LTV, CAC, payback, and ARPU, check out this post I wrote previously on the topic. Below is a handy LTV model you can play with as well.

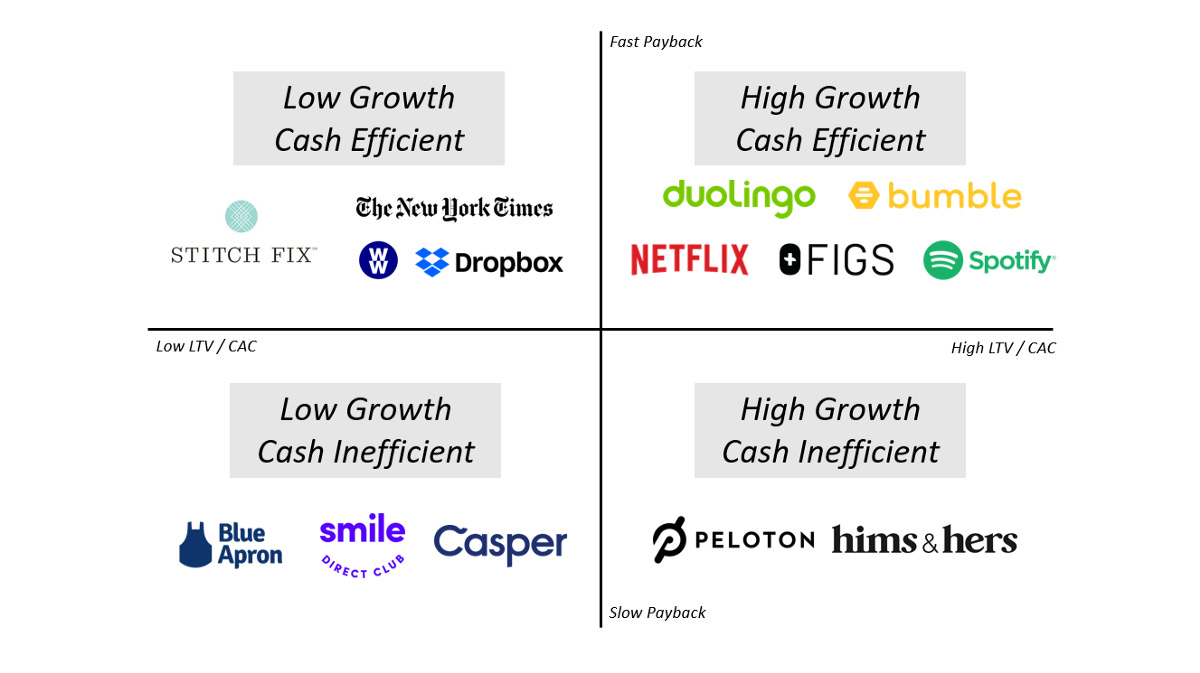

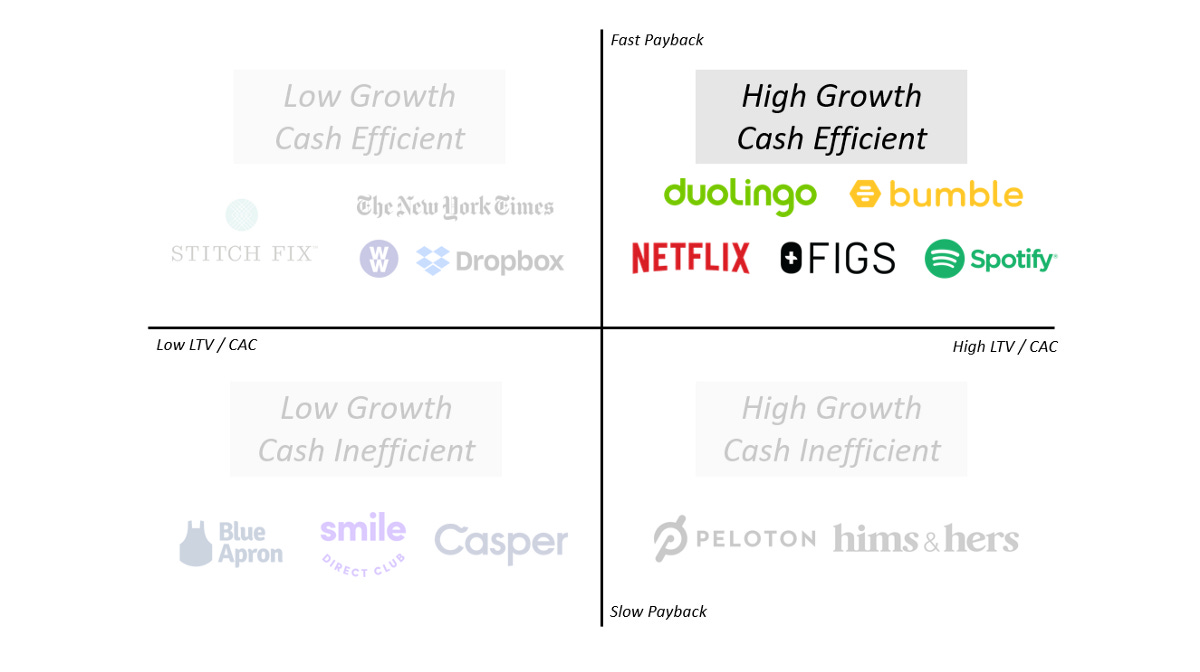

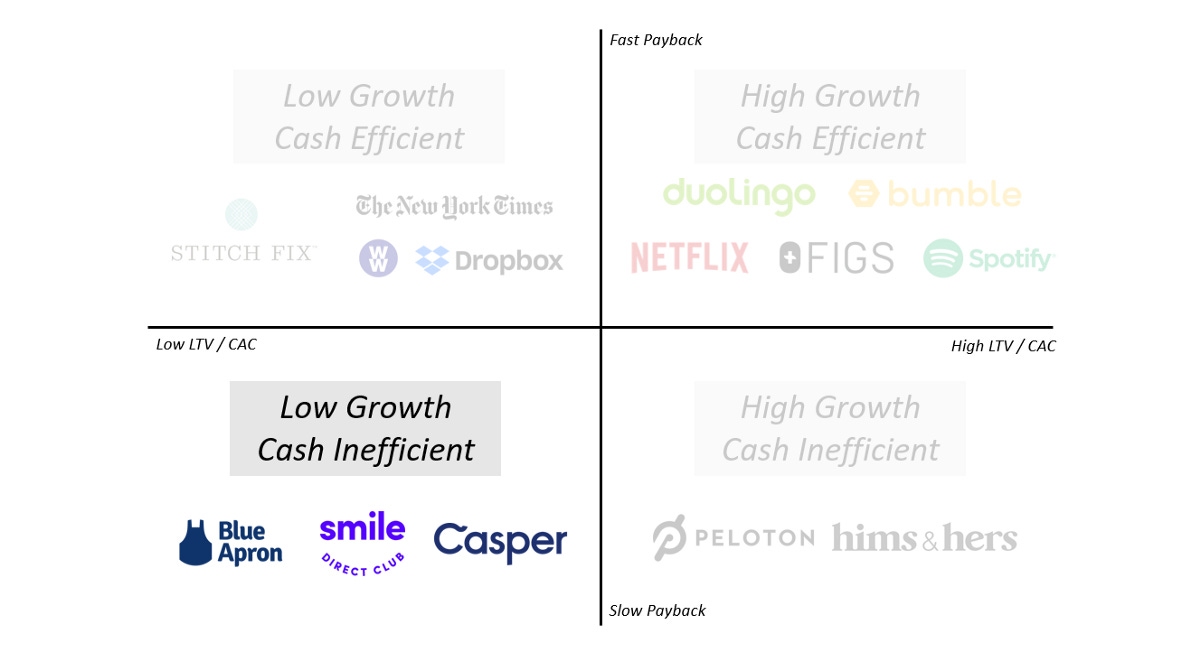

High-Growth, Cash Efficient

The companies in this top-right quadrant are high performers. Every business strives to live in this quadrant. These companies have both strong LTV / CAC dynamics and fast payback. They get here by operating in large markets, having high frequency user engagement, flattening retention cohorts, and high gross margins. As a result of fast payback, they can recycle cash and re-invest into product and marketing to drive growth, develop new growth engines, all while maintaining strong profit margins. These strong business fundamentals are rewarded in the public markets with premium valuation multiples.

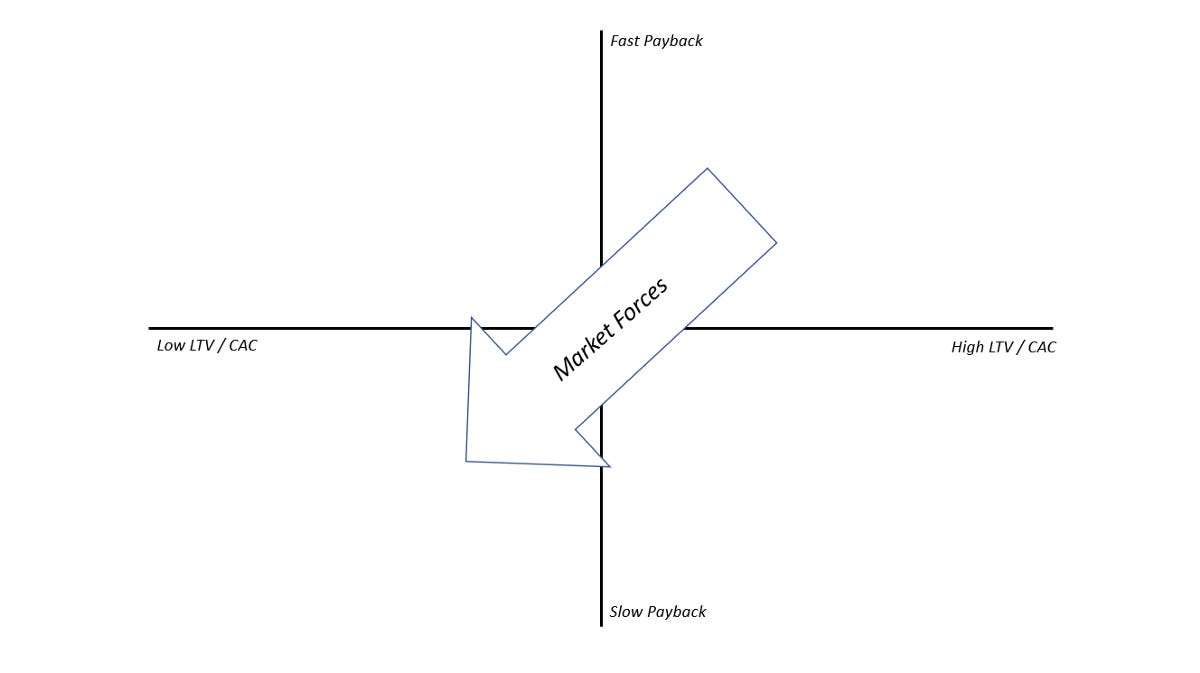

But being in this quadrant doesn’t mean a company will stay here forever. These companies must push against market forces that will naturally erode their unit economics in multiple ways:

LTV decreases: 1) As companies acquire more adjacent customers, retention will degrade. 2) Technological advancement and changing consumer preferences influence usage patterns and spending behavior.

CAC increases: 1) CAC will naturally increase as companies invest and saturate their core marketing channels. 2) Growth will attract capital and competition to the market, making it more expensive to acquire customers.

In order to remain in the top right quadrant, companies must either improve LTV by increasing gross margins, expanding ARPU with new products, improving retention, or they must find more efficient acquisition channels to reach new customers.

High-Growth, Cash Inefficient

Companies in the bottom-right quadrant have high growth potential due to strong LTV/CAC dynamics but given the slow payback, will require significant working capital to scale. Many venture-funded startups begin their journey in this quadrant. Let’s walk through an example of what it means to have slow CAC payback and the cash efficiency implications for a business:

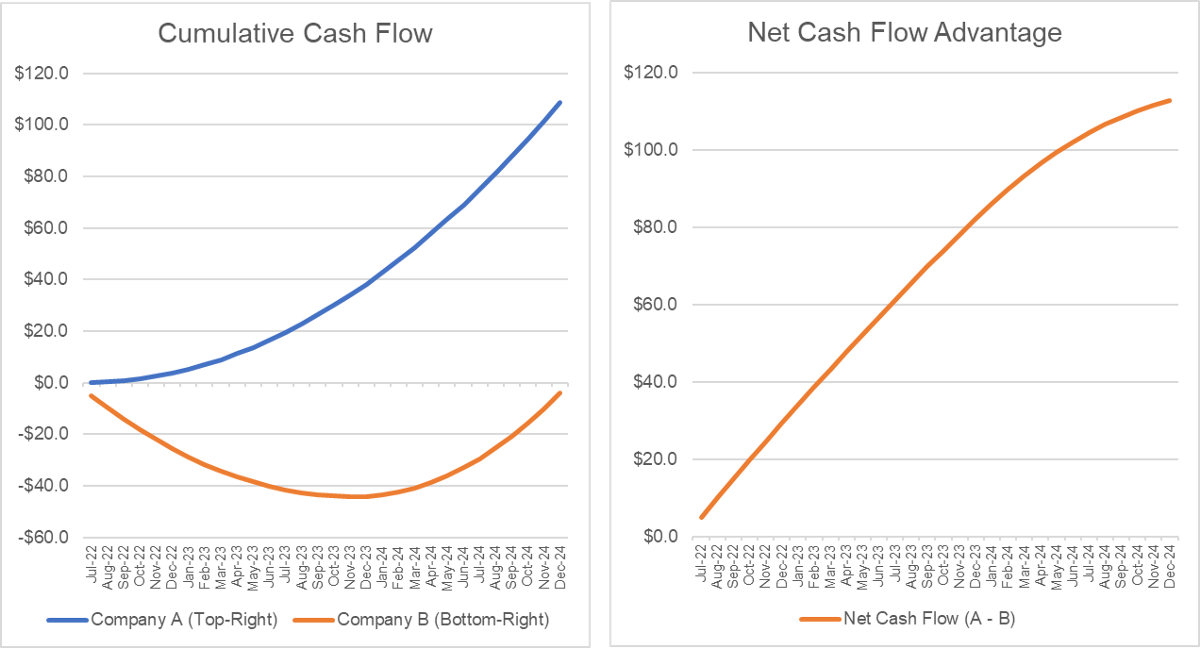

Company A has 3x LTV / CAC but with month 1 payback (top-right quadrant — fast payback)

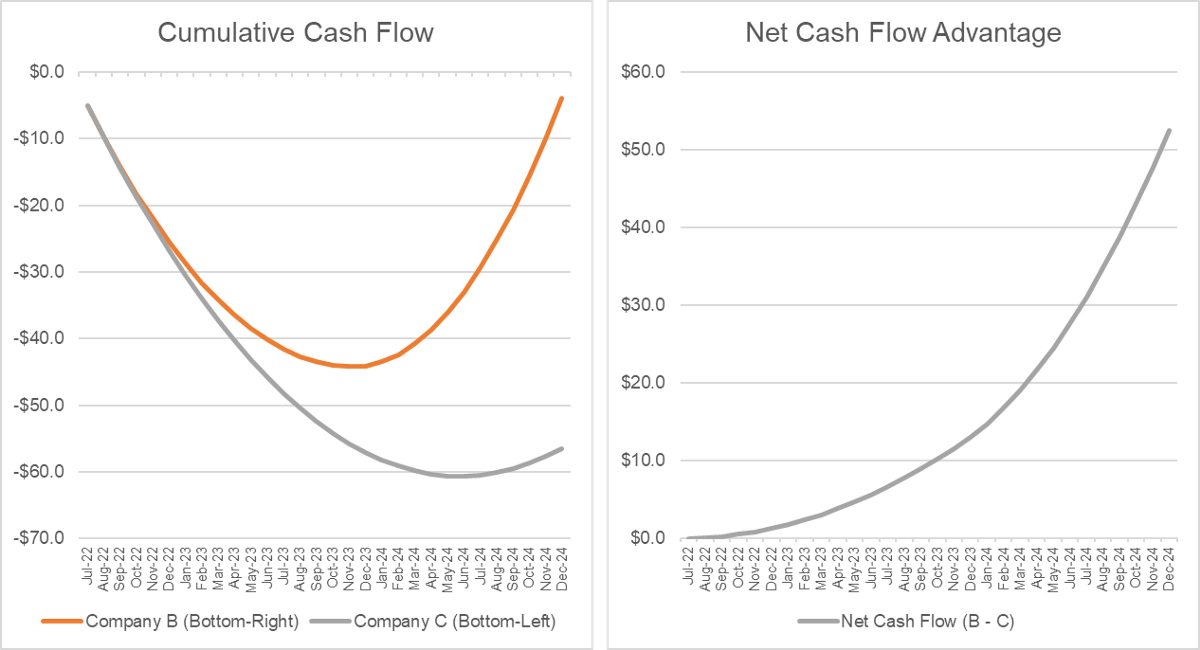

Company B has 3x LTV / CAC but with month 18 payback (bottom-right quadrant — slow payback)

If you were running company B and invested $5 million in a given month to acquire a cohort of users, you would have to wait 18 months before you received the $5 million back and even longer to generate profits. Conversely, if you were running company A, you would recoup your $5 million investment in month 1. Now let’s imagine you invested $5 million every month for the foreseeable future to acquire customers at each company. There is a compounding effect. With strong LTV/CAC it might make sense to make these investments over the long-term, but it comes at a high cost of capital.

In the illustration below, you will see that by December 2024, company A has generated $110 million of cumulative cash flow from its marketing investments whereas company B is still in the red, having lost $4 million. Company B also has a cash low point of $45 million, meaning it needs to rely on external funding to support its growth. Given company A’s cash efficiency, the team is not reliant on external funding to grow and can re-invest the cash flow generated into product or other areas to drive more growth. It has a significant cash advantage. During 2020 or 2021, this strategy could have potentially worked out for company B— growth capital was abundant and the return of the risk-free alternative was near 0%. The cost of capital was cheap! But in the new era we’re facing, company B faces tougher decisions. Which business would you rather be running? How would you respond?

Companies that are able to successfully navigate this quadrant must demonstrate strong and flattening (vs downward-sloping) retention cohorts in order to sell the promise of long-term value creation. Flat cohort curves provide a healthy base of users to build product and growth strategies on top of. This takes pressure off new user acquisition and leads to predictable growth and strong long-term margins. Only companies with these fundamentals will secure adequate financing in this environment.

Low-Growth, Cash Inefficient

This quadrant is the “danger-zone” where companies have both low LTV / CAC and slow payback. Let’s continue with our example.

Company C has 1.5x LTV/CAC and 24 month payback (bottom-left quadrant)

Company C faces a really difficult cash situation. By the end of 2024, the company is down $58 million of cash and is only just starting to recoup its investments. While Company B is also in a difficult cash position, it is buoyed by strong LTV / CAC which over time helps drive cash flow to offset its investments. This is why the curve slopes upward more quickly. If you thought company B would have a tough time fundraising, in the current macro climate, company C will face a down-round or, even worse, go out of business unless they take serious action.

Companies ultimately end up in the bottom-left quadrant because of poor business fundamentals: weak retention, limited product differentiation, pressured gross margins, and high cost of user acquisition. These companies are highly reliant on outsized marketing spend to drive growth. As aggregate marketing spend goes up, CAC follows, leading to lower LTV / CAC and even slower payback periods — this is a brutal negative cycle. Given these poor fundamentals, external capital is needed to stay afloat but often a challenge to secure. These companies are forced to cut their marketing spend and run lean to manage their burn. Getting to profitability, if even possible, comes at the significant cost of growth, moving these companies to the top-left quadrant.

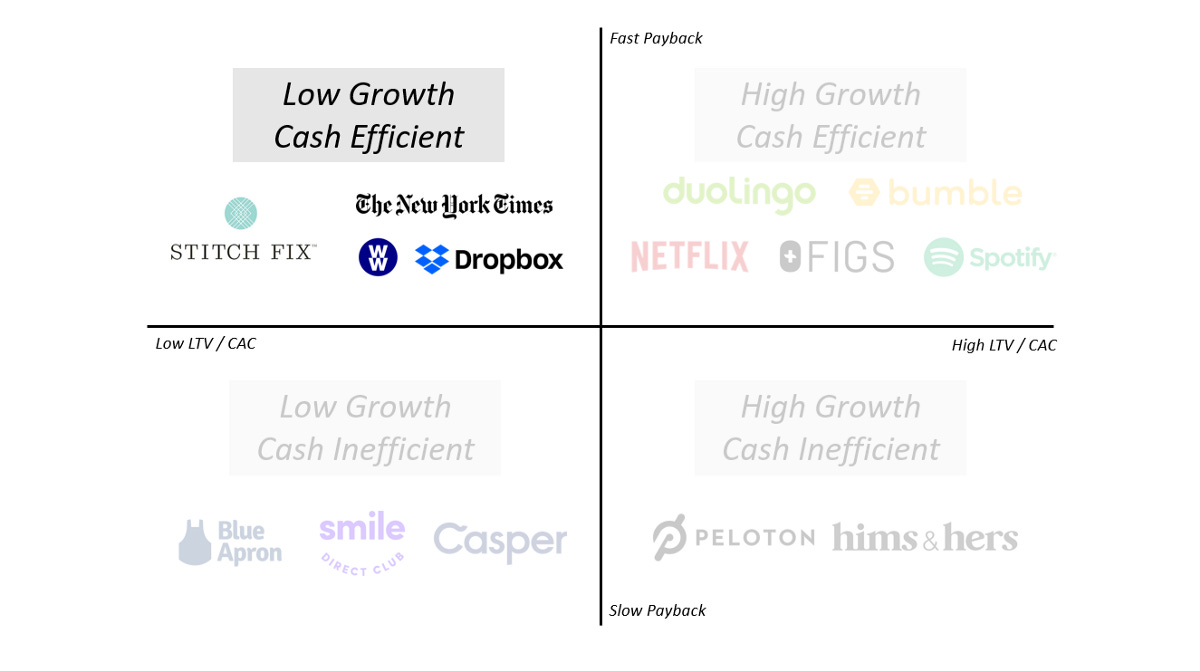

Low-Growth, Cash Efficient

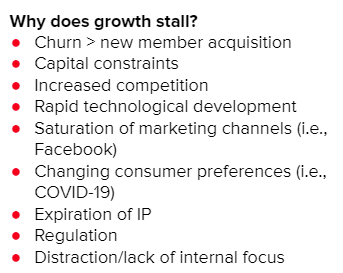

Many direct-to-consumer startups will inevitably reach a point of maturity and end up in the top-left quadrant. Some get pushed here directly from the top right quadrant while others take a different path. Products with weak retention will reach this maturity phase very quickly (e.g., transactional e-commerce businesses). But even products with strong retention will inevitably face headwinds that slow growth and make it progressively more challenging and expensive to grow profitably at scale. Below are a few examples of market forces that can stall growth and degrade economics:

The companies with the most defensibility through network effects, product differentiation, or other moats can succeed in counter-acting these pressures and staying in the top-right or bottom-right quadrants.

The Startup Journey is Ever Evolving

Nothing is static. Every company, product, business line, and pricing plan moves uniquely through this 2x2 matrix during its lifecycle in different ways. Most notably, COVID-19 changed consumer preferences and pushed Peloton up to the top right quadrant for a couple years, but they now find themselves in the bottom-right quadrant. Conversely, Hims & Hers recently had a strong quarter and might have moved itself up into the top-right quadrant. Let’s walk through a few more detailed examples to illustrate this:

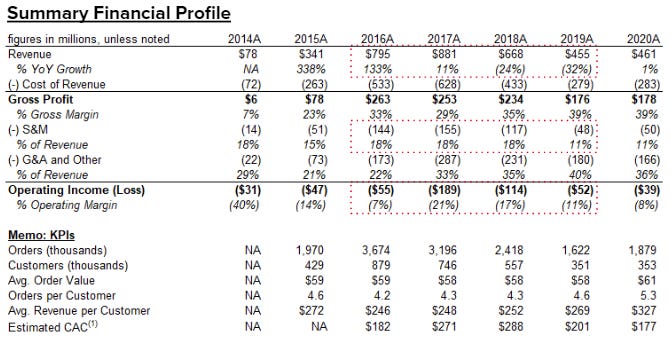

Company — Blue Apron

Blue Apron once started as a high-growth business, growing 4x year-over-year in 2015 with moderate losses. They were in the bottom-right quadrant and raised a private round at a $2B valuation. Underneath, however, they had poor fundamentals: low gross margins, poor retention, and rising operations costs. Given the weak retention, they were reliant on marketing spend to drive growth. But as they scaled marketing acquisition in 2016 and 2017, their cost of acquisition increased significantly given the saturation of their core channels. They no longer had a viable business — LTV/CAC was upside down. Growth plummeted and losses ballooned. They quickly found themselves in the bottom-left quadrant and their stock plummeted as a result by over 80% in the year after IPO.

To make matters worse, to get out of this hole they started discounting heavily. While this drove short-term sales, it worsened their problem in the long-term as it brought in even lower quality customers. Many of these customers found the price-level too expensive once the initial coupon or sign-up promos ran out and churned. Currently, Blue Apron is in a tough position. In order to manage their burn, they have dialed back marketing spend even further, but at the significant cost of growth. To stay solvent, they have no choice but to cut costs even further and focus on high-quality customers to move to the top-left quadrant. The question remains if they will be able to get there. With no growth or profits, investors don’t see much value in this company and as a result, Blue Apron is left with a market capitalization of <$100M. Ouch!

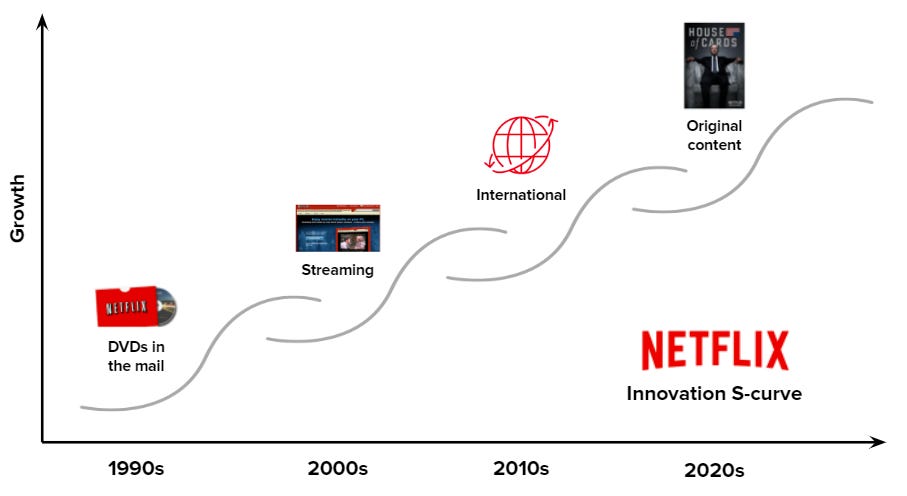

Product / Business Line — Netflix

The highest-performing companies are able to invest in new growth engines to drive durability over many years. Netflix is a perfect example of a company that has a successful history of “jumping” S-curves. More on this concept of S-curves here. Over several decades they have navigated technological change, changing consumer preferences, competition, market saturation, and more. Each of these initiatives was an S-curve that went through its own journey across multiple quadrants. While many of these initiatives perhaps individually ended up in the top-left quadrant, collectively, they have kept Netflix as a company afloat in the top-right quadrant.

Pricing — Duolingo

Duolingo operates as a freemium business and generates revenue from its premium service, Duolingo Plus. Members can subscribe to this pricing plan for $13 per month or $80 per year if paid annually. The annual plan comes out to an almost 50% discount on a monthly basis. Duolingo prices this way by design to drive members to purchase annual plans. In fact, annual plans are now 85% of subscribers, up from 71% one year ago. This is likely because Duolingo’s monthly plans have weak retention and would make it hard for the company to grow sustainably if this was the only plan they offered. Annual plans lock-in members for a full year upfront and enable Duolingo to collect cash on day one, covering their cost of acquisition. The annual pricing plan is in the top right quadrant whereas the monthly plan is not.

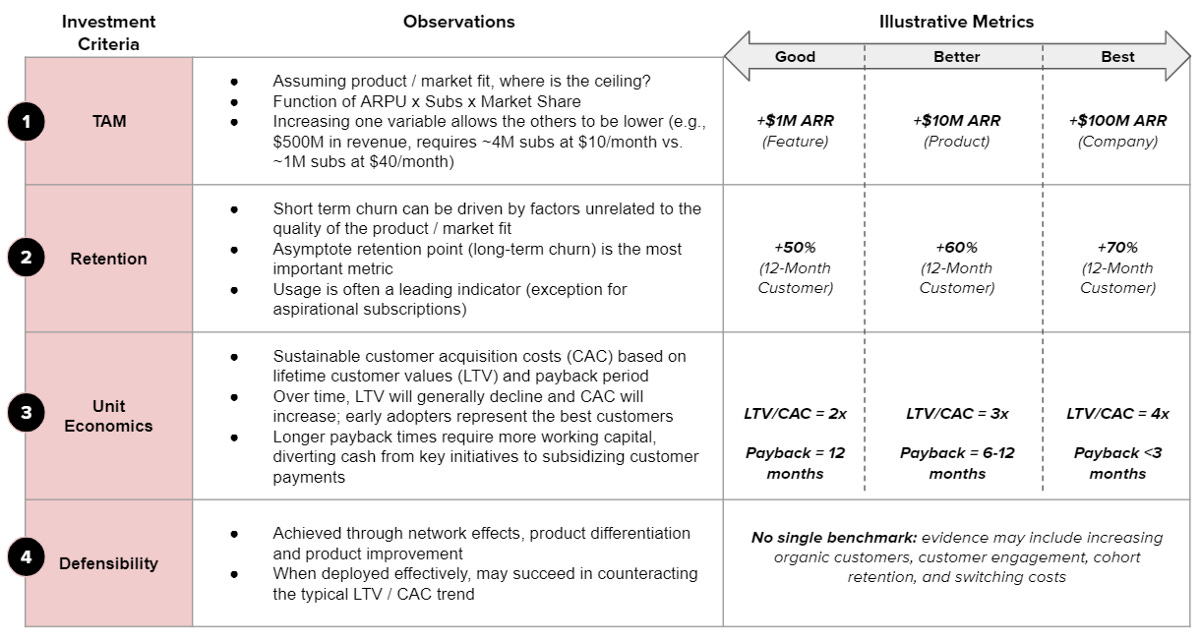

Key Benchmarks

Now that we’ve discussed how CAC payback and LTV/CAC influence growth and profitability, what are some benchmarks to follow? The best companies in the top-right quadrant are able to demonstrate 60%+ retention with flattening cohorts, 3x+ LTV / CAC, with less than 6 months payback. They also have moats in place to defend against natural headwinds. If you find that your company has annual retention less than 40%, LTV/CAC less than 2x, or CAC payback longer than 12 months, it is worth investigating your fundamentals in detail.

For more detailed reading on subscription KPI benchmarks, please refer to my prior post on the topic.

Special thanks to several of my colleagues Sam Bauman, Kim Larsen, and Amit Bhatt for their contributions to this post and to Lazard for supplying benchmarking data.